Independent Review of the M/V Marathassa Fuel Oil Spill Environmental Response Operation

Chapter 3 - Observations, analysis and recommendations

Table of Content

3.1 Discharge

Key facts

According to information available to the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG), the M/V Marathassa left the shipyard in Maizuru, Japan on March 16, 2015, to embark on her maiden voyage, with an expected date of entry into Port Metro Vancouver (PMV) on April 6, 2015.

It is believed that the discharge of fuel oil was released intermittently into the marine environment from the M/V Marathassa during the afternoon of April 8, up to the early morning of April 9, when the vessel was boomed. An aerial observation of the vessel earlier in the day at approximately 11:00h indicated that there was no pollution observed; the vessel was washing down some of its compartments and discharging water into the harbour as per normal procedures.

Transport Canada (TC) is currently leading an ongoing investigation concerning the events leading up to the discharge of fuel oil into English Bay, as per their regulatory role. As such, this review will not examine the nature or cause of the spill.

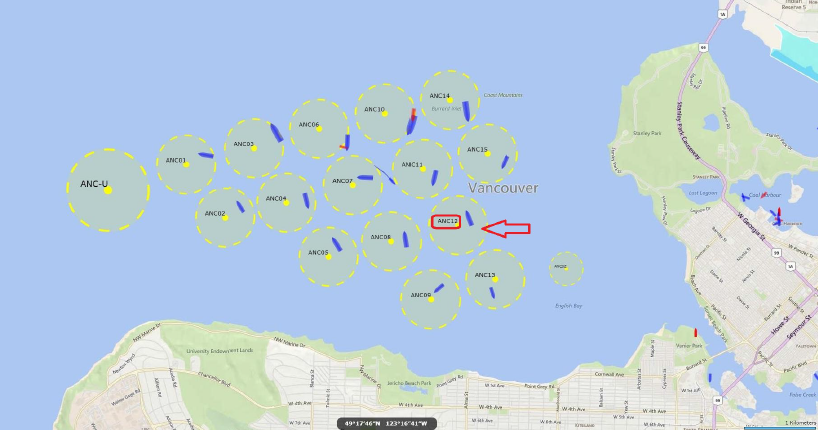

M/V Marathassa's position: anchorage 12, English Bay

3.2 Notification

Key facts

The discharge of fuel oil in English Bay was first detected by a sailing vessel (Hali) and reported to the CCG Marine Communications Traffic Services (MCTS) at 16:48h. Subsequent observations of an oil sheen by other sailing vessels and the public were reported to the Vancouver Police Department and 911, which were then provided to the CCG. These reports indicated extensive sheening and tar balls in English Bay near anchorage 12, the location of the M/V Marathassa.

The initial notifications were then provided to PMV and the CCG’s Environmental Response (ER) Duty Officer located in Prince Rupert for further assessment and potential action. The CCG receives an estimated 600 marine related spill reports on the coast of British Columbia (BC) that require investigation and assessment each year, approximately 40 of which are in PMV.

Internal Notification

The CCG utilizes an internal notification process called the National Incident Notification Procedure (NINP), the purpose of which is to provide the CCG and Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) Senior Management with an immediate initial alert to inform the organization that an event of significance has occurred or is occurring. Footnote 21

The NINP was generated within the first hour after the CCG activated WCMRC. It was sent to the MCTS Centre for national distribution via email at 21:05h, and transmitted to the distribution list at 22:09h by email only. The recipients of the NINP included all CCG Senior Management, departmental officials nationally and the CCG’s National Coordination Centre (NCC) in Ottawa.

The NCC Duty Officer is responsible to take appropriate action, as required, such as notifying senior management. During standby hours (beyond regular working hours), such as in this incident, email notifications are not required to be read until the following morning. If the event is determined to be of national significance, then a phone call is required. In the case of the M/V Marathassa, no verbal notification or phone call was initiated by the region.

Notification of Key Partners

Once preliminary information regarding the fuel oil spill was confirmed with the initial sailing vessel (Hali) who reported the spill, the MCTS Centre initiated a fan out notification process, as per standard operating procedures, and forwarded a pollution report to key partners at 17:10h. These partners included DFO, Environment Canada (EC), TC, the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre, PMV, and Emergency Management British Columbia (EMBC).

When EMBC receives a pollution report, it is sent to its 24/7 provincial Emergency Coordination Centre (ECC), who then contacts the Environmental Emergencies Response Officer (EERO). As per EMBC’s protocols, an assessment by British Columbia’s Ministry of Environment (MOE) is conducted in order to determine its code level and whether email or verbal notification is required. Code 1 reports, which are deemed minor, are distributed internally to the organization for information, whereas Code 2 reports require further distribution to First Nations, other provincial departments, municipal governments, and other affected partners. A Code 2 is also triggered when a request for the MOE’s services is made to increase the incident classification, which was not immediately made in this case. Footnote 22

The initial pollution report indicated that there was approximately 200 square meters of sheen and possible bunker C fuel oil extending from the stern of the M/V Marathassa, and that the incident was being assessed by PMV. A second pollution report was distributed at 19:40h indicating that the spill was deemed non-recoverable, approximately three hours after the initial notification. Based on this information, MOE assessed the incident to be a typical sheen, identified it as a Code 1, and noted that the PMV vessel had stood down. The Code 1 internal notification was distributed at 19:48h and no further fan out notification to other partners was distributed at the time.

The CCG received information that the spill was non-recoverable based on information inaccurately relayed from the PMV vessel to the CCG via Western Canada Marine Response Corporation (WCMRC). This alternating assessment propagated through the notification system and may have created confusion for the Duty Officers trying to evaluate the significance of the incident.

A third pollution report was then distributed by CCG at 21:04h indicating that the spill had been reassessed following receipt of aerial surveillance photos and had been upgraded to recoverable. The report also noted that WCMRC had been contracted to respond and clean-up the fuel oil.

At 03:07h on April 9, the CCG spoke with the EERO to request their on-scene presence, once it was determined that the spill was of higher significance. The CCG indicated that a representative would not be required until first thing in the morning. The incident was not officially upgraded to a Code 2 until 15:27h on April 9.

Most partners were notified of the incident on the morning of April 9 from a variety of sources, including the WCMRC, the City of Vancouver, MOE, and the media. MOE internal notification confirmed at 10:11h on April 9 that the First Nations, Vancouver Coastal Health, Oiled Wildlife Society and the Vancouver Aquarium had been officially notified.

Observations & Analysis

Internal Notifications

The National Incident Notification Procedure (NINP) was established several years ago to avoid regional variability of the national alerting process and to ensure that senior management has up-to-date accurate information regarding a serious incident as it develops. The criteria for determining an incident of significance has, in the past, been an effective mechanism of managing and sharing information, particularly in the early stages of an incident. However, in this case, the NINP process did not effectively alert the CCG Senior Management, as no verbal notification or phone call was received indicating the extent of the spill and the potential impact on the Vancouver Harbour and surrounding communities, although the NINP indicated that high media attention was anticipated.

The NINP is typically drafted by regional Environmental Response staff and approved by the regional CCG Senior Management. The criteria are fairly clear in identifying when a NINP should be triggered, such as in this case where persistent fuel oil in a confined harbour and bay had the potential of reaching adjacent beaches. There is, however, a category of events in the NINP procedure that indicate when an event of significance does not require verbal notification to the CCG Senior Management, which appears to be at odds with the intent of the NINP and early and accurate dissemination of information to the required senior officials. Regional officials indicate this was not a factor in this case.

Verbal notification was not initiated due to the fact that written notification was already sent and that operations were well in hand and partners were alerted. The intense public reaction was not anticipated and the net result was that the CCG Commissioner was not made aware of the significance of the spill until the morning of April 9, due to heightened media attention. Alerting the CCG Senior Management in Headquarters earlier may have provided DFO Communications the opportunity to proactively support the organization, including identifying that the CCG was the lead agency.

Recommendation #1 - The National Incident Notification Procedure criteria and the exemptions for verbal notification should be reviewed to ensure all significant incidents receive verbal notification 24/7 to the senior national leadership of the Canadian Coast Guard.

In addition, the NINP process enables other regions to develop potential support plans early should a National Response Team be necessary for an incident. This is expected in a major environmental response incident, as regional capacity is limited requiring the cascading of personnel and equipment. For example, during the Brigadier General Zalinski (BGZ) oil removal operation in 2014, personnel were successfully cascaded from across the country.

External Notifications

As noted, EMBC and MOE are currently responsible for determining the appropriate fan out process as part of their regional alerting process. While the notification and fan out process followed all existing standard operating procedures, it was not effective in immediately identifying the incident as significant. As per MOE’s written notification protocols, an incident should be upgraded to a Code 2 once their services and presence are requested. However, given that in the early stages it was still not clear that the spill was significant, the incident was not upgraded to Code 2 until Thursday at 15:27h by the province. As such, First Nations, provincial and municipal partners were still not officially notified of the event unfolding in English Bay until the following day.

Most partners were notified of the spill early on the morning of April 9 via informal channels, primarily due to already-existing working relationships, and were not informed via the proper notification protocols. Additionally, many partners noted that email notification was insufficient, as they do not reflect the urgency or significance of an event, particularly if they are received during non-business hours. Furthermore, multiple key partners are not included as part of any formal notification process of oil spills in PMV, despite their significant professional expertise in areas such as oiled wildlife and scientific research.

The provincial government maintained the Code 1 classification following the third pollution report received at 21:04h, even though it indicated that the spill was more significant than originally thought. At present, the criteria for assessing whether an incident should be escalated to a Code 2 does not take into consideration the location and potential consequences of a spill; however, the province’s risk assessment of oil spills does include these as risk factors. Had MOE re-assessed the incident to include these factors, as well as the potentially high media attention, a Code 2 may have been called, leading to a broader fan out of the incident to those who could be impacted by the spill. This notification to other levels of government and other partners would also have indicated that the CCG was taking the lead in addressing the marine pollution. However, it is clear that EMBC and MOE may not have had the most current information to make informed decisions regarding its notification classification.

This early notification may also have provided confidence that the CCG was leading the response and could have reduced negative public communications in the media.

Recommendation #2 - The Canadian Coast Guard, Emergency Management British Columbia and British Columbia Ministry of Environment should jointly review alerting and notification procedures to promote a common understanding and approach between the organizations when assessing and notifying regarding marine pollution incidents.

3.3 Assessment

Key Facts

The initial pollution report was of a 200 square meters of sheen from the starboard quarter as the sailing vessel transited the area. The sailing vessel drifted back across the area not seeing any major concentration. The second vessel to report the spill and transit the area reported a smell of asphalt and a larger slick of 250m by 0.5 km with tar balls of various sizes.

Upon receiving this information, a PMV vessel was tasked to collect information at 17:10h, as per a Letter of Understanding (LOU) between CCG and PMV. To collect information, PMV surveyed the immediate area around the anchorages to determine the extent of the spill, including speaking with the sailing vessel (Hali) who had originally reported the pollution to identify where there was believed to be a higher concentration of fuel oil. PMV attempted to identify the source of pollution and contacted Nav Canada Vancouver Harbour Control Tower for aerial surveillance. PMV also aimed to determine if the pollution was recoverable by deploying sorbent pads into the water.

The Captain of the vessel was denying it was the polluter, but acknowledged that there was fuel oil around his vessel. Following the collection of information, PMV determined that the fuel oil spill was recoverable and alerted CCG’s MCTS Centre at 17:58h, requesting a CCG response vessel.

The MCTS Centre then notified the CCG ER Duty Officer. In direct discussion with the port, the ER Duty Officer suggested that they contact WCMRC directly and indicated that it would take 60-90 minutes for a CCG Response Specialist to arrive on scene. During that time, the CCG Superintendent, ER, received the pollution report from the Duty Officer and immediately contacted WCMRC at 18:08h to inform them that their services were likely going to be required to clean up the spill. They were not yet officially asked to activate resources, yet indicated that they were prepared to mobilize.

PMV then contacted WCMRC via their activation line at 18:25h. Five minutes later, PMV Operations discussed the fuel oil slick of recoverable pollutants in English Bay with WCMRC, who advised them that arrival time was 90 minutes. WCMRC subsequently decided to mobilize resources and was prepared to use this opportunity as an exercise.

PMV then re-surveyed the anchorages and re-checked the area of major sheen from 18:30-18:45h, attempting to locate the source of the pollution, and indicated they did not locate any other large pools of fuel oil. Although the previously deployed sorbent pads recovered fuel oil, PMV was unable to locate the original large concentration of fuel oil, nor the source.

At 19:03h PMV contacted WCMRC and discussed what they had observed. The PMV vessel was concerned about diminishing daylight and returned to the dock to obtain sampling kits. This communication was perceived by WCMRC to mean that PMV was standing down as there was no recoverable oil. This was in error. Due to miscommunication, WCMRC demobilized and communicated this to the CCG Superintendent and Duty Officer, leading to de-escalation in the significance of the incident. As the lead agency, the CCG accepted this information without verification from the source, PMV.

Based on the information received from WCMRC, MCTS distributed another pollution report at 19:40h noting the change in assessment to non-recoverable, approximately three hours after the initial notification from the sailing vessel (Hali). The provincial notification process also updated its report to indicate that the PMV vessel had stood down due to unrecoverable fuel oil. No further notification of municipal and other partners was necessary. Unfortunately, this information was in error due to the miscommunications and was passed erroneously through the notification system.

While the notification fan out process was in progress, PMV received photos from a private Cessna aircraft indicating the extent of the fuel oil spill. At this time, PMV Operations and the on-duty Harbour Master discussed various actions, including boarding the M/V Marathassa and calling both the CCG and WCMRC. The Harbour Master called WCMRC to inform them of the aerial surveillance photos they had received. PMV informed MCTS at 19:51h that they were unable to reach the CCG Duty Officer (and were informed it was due to technology and connectivity issues), and noted that the photos received from the Cessna aircraft indicated a larger spill than originally thought.

Once the CCG had an opportunity to review the photos at 19:55h, they officially contracted WCMRC, who confirmed a few minutes later that they were mobilizing their resources.

Another pollution report was then distributed at 21:04h to indicate that the spill had been re-assessed and upgraded to recoverable due to new information from aerial photos. The report also noted that WCMRC had been contracted. At 21:31h, MOE released an updated report, noting that the spill was larger than originally thought; however, the report was not upgraded to a Code 2. As such, no further fan out of information was provided to First Nations, provincial partners and municipal governments.

Observations & Analysis

It appears that the CCG ER staff were operating under the assumption that PMV was responsible as the spill was located in the port. However, in all mystery marine spill incidents, the CCG is the lead federal agency for ensuring an appropriate response. Given that the M/V Marathassa had not yet been confirmed as the polluter, the CCG was, in fact, the lead agency.

This misunderstanding was likely due to two key factors. First, there has been a significant changeover in staff in the CCG’s ER Program. Second, the Duty Officer was physically located in Prince Rupert and may not have been appropriately made aware of the existing roles, responsibilities, and authorities in PMV with respect to oil spill response and had not been made aware of the appropriate protocols in the event of a mystery oil spill.

Despite these two factors, CCG management is required to ensure that officers review and understand their roles and responsibilities.

PMV operates under its own letters patent, the Canadian Marine Act and all associated regulations with authority to address pollution incidents within its boundaries. A LOU with the CCG has clarified this authority, noting that PMV will collect the appropriate information regarding reports of pollution and hand over the command once it is determined that the spill is recoverable. Information collected includes collecting samples, deploying sorbent pads, on-water visual sightings, and requests for aerial surveillance. PMV indicated that they are currently considering newer technologies to assist in assessment such as Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) that could prove very beneficial in the future.

Concerns were raised by partners that PMV may not be the best-equipped organization to assess marine pollution incidents. In particular, participants raised concerns regarding PMV’s ability to respond to oil spills and their training requirements. PMV vessel Masters are certified vessel operators, with a 60T limited masters certification with TC. Footnote 23 In addition, the port has experience with ship-source pollution in the port and working with WCMRC, enabling them to provide the best information possible to the CCG regarding potential pollution incidents. Additional exercising, however, would benefit partners ensuring all are aware of their roles.

In this instance, PMV believed that it was to collect information only, and would transfer the information over to the CCG who would make an assessment and would take over responsibility and command of the response to the mystery spill.

The lack of clarity by the CCG regarding its roles and responsibilities in the port led to both the CCG and PMV directly contacting WCMRC. WCMRC had initially been alerted by the CCG but a response had not been activated. A follow up discussion with PMV, who also did not activate the Response Organization, left uncertainty between the respective partners. In the absence of activation by either the CCG or PMV, WCMRC responded by mobilizing their response personnel as an exercise. This was a precautionary measure taken by WCMRC. Since PMV had requested a response by the CCG at 18:05h and the mobilization decision by WCMRC was only taken at 18:35h, this represented a delay of approximately 30 minutes. WCMRC was still not activated; however, they had notified the CCG that they were mobilizing as an exercise.

WCMRC mobilization continued at the Burnaby base as employees prepared to engage in a response exercise. PMV also continued its on water assessment operations in an effort to locate any further recoverable oil and locate the source of the pollution.

Communications with the CCG Duty Officer were limited at this time due to issues with his cellular phone.

At 19:03h PMV calls WCMRC for additional advice on what they are observing on the water. During this conversation it is understood by WCMRC that the port is unable to find any further recoverable oil and that they are standing down. This was a communications error between the PMV vessel and WCMRC. What had been intended to be communicated was that the PMV vessel was not observing any recoverable oil at that time and that they were returning to its base to obtain a sampling kit to collect samples of the pollutant to enable future matching with the polluter. The message that they were standing down was not the intent. This communications error between the port and the WCMRC was then communicated to the CCG. The effect of this miscommunication was that WCMRC began to demobilize from its planned exercise.

Often reported spill assessments change with further on water surveys so this reassessment by the port would not be uncommon and was accepted by the WCMRC. This miscommunication was shared with the CCG and they began de-escalating the incident and communicating this through the notification system to other federal and provincial partners. The CCG should have contacted PMV directly to verify this change in direction. In contrast to the miscommunicated message, and perception that PMV was standing down, PMV was actually continuing the on water operations. The demobilization of WCMRC at 19:03h and their subsequent activation at 19:57h represents a further delay of 54 minutes.

As part of PMV’s ongoing assessment of the spill they had requested photographs of the area from transiting aircraft. This is the best method of determining the extent and nature of the pollution.

At 19:27h pictures received from a private Cessna aircraft clearly show the extent of the sheen and concentrations of recoverable oil. PMV’s first call is to WCMRC to confirm that they are activated by the CCG. PMV is unaware of the demobilization that has occurred, as they were not aware of the effect of the miscommunications between the PMV vessel and WCMRC. PMV also calls the CCG with its new information at 19:45h but due to continuing connectivity difficulties has to call an alternate number. When contact is established the Duty Officer has difficulties viewing the pictures on his mobile device and has to view the new information on his personal computer. The photos are eventually shared at 19:55h.

The pictures and their assessment by the Duty Officer trigger an immediate response by the CCG. At 19:57h WCMRC is activated and is able to respond faster than the normal 60-90 minute mobilization time as the staff have just left the base and are immediately recalled. The remobilization occurs in 48 minutes and WCMRC is on scene at the M/V Marathassa at 21:25h, 1 hour and 28 minutes after activation.

A combination of these factors caused a delay in the response. Initially, the lack of clarity on the respective roles and responsibilities followed by a miscommunication between WCMRC and the PMV vessel and then connectivity issues. The earliest possible activation time of PMV was at 18:08h when the CCG provided a notification to WCMRC, the actual activation occurred at 19:57h by the CCG, 1 hour and 49 minutes later.

In difficult cases, experience has shown that it is often best to assume the worst and activate the response while the assessment is continuing, particularly in areas of high consequences, such as the PMV. The precautionary principle prevents surprises in possible worst-case scenarios.

Recommendation #3 - The Canadian Coast Guard and Port Metro Vancouver should review the Letter of Understanding to clarify their respective roles and responsibilities within the port waters.

Recommendation #4 - Port Metro Vancouver should continue to collect information regarding reports of marine pollution under its area of responsibility and to request aerial surveillance to support the Canadian Coast Guard’s effective assessment of marine pollution incidents.

Recommendation #5 – The Canadian Coast Guard should ensure that Port Metro Vancouver has the appropriate information, training and standards to assist their staff in performing assessments.

Recommendation #6 – The Canadian Coast Guard should ensure that all Environmental Response staff review the appropriate agreements to ensure clear communications between the Canadian Coast Guard Duty Officer and Port Metro Vancouver and to review roles and responsibilities in oil spill response within the boundaries of Port Metro Vancouver.

Recommendation #7 – The Canadian Coast Guard should review the assessment procedures with staff and ensure they are empowered and supported to take a precautionary approach when assessing reported spills, even if it means from time to time the system will overreact.

3.4 Initial Response

Key Facts

At 19:57h the CCG activated WCMRC to clean up the fuel oil spill, and by 20:45h, approximately 48 minutes later, resources were mobilized, arriving on scene at 21:25h to immediately begin containment and recovery.

The CCG Senior Response Officer (SRO) in Vancouver was contacted at 20:38h, transferring the lead from the Duty Officer in Prince Rupert. The SRO immediately proceeded to PMV and was briefed. He then took charge of the response and commenced routine response activities. This included contacting WCMRC to assist in determining the appropriate response measures, contacting Environment Canada’s (EC) National Environmental Emergency Centre (NEEC) to understand the risks (i.e. requesting trajectory modelling and environmental sensitivities for the PMV and surrounding areas) to facilitate response. The SRO also contacted the Vancouver Police Department to inquire whether they had received any fuel oil spill calls in the English Bay area. There were none.

The CCG SRO then boarded the vessel with a PMV representative and issued a Letter of Undertaking at 00:45h, asking the Captain to respond with the vessel’s representatives’ intentions for clean-up by 05:00h on April 9. The fuel oil was not yet confirmed as coming from the M/V Marathassa and the Captain denied that the vessel was the source of pollution. The SRO also checked with WCRMC to confirm that the clean-up operation was well underway and requested a NOTSHIP for vessels to reduce their speed while transiting English Bay to reduce the spread of fuel oil.

WCMRC continued its recovery operations throughout the night, including using a vessel equipped with a forward looking infrared camera. As the overnight operation continued, adjacent vessels were searched to identify the source of pollution; however, crews returned to the M/V Marathassa, as that is where the highest concentration of fuel oil was. Fuel oil was seen welling up from the stern of the vessel and a WCMRC infrared camera confirmed that the vessel was the source of the pollution. The CCG SRO then requested that WCMRC begin booming the vessel at 03:25h, which began at 04:36h and was completed by 05:53h to contain the source of fuel oil. Skimming then continued at the scene and inside the boom surrounding the vessel.

Priorities for the morning were discussed between the CCG and WCRMC, including obtaining aerial surveillance, as this is the best tool for determining the movement of oil, and focusing on sensitivity mapping, which was essential in planning response operations.

Observations & Analysis

In most ship-source pollution incidents, the Responsible Party (RP) or the polluter is readily identifiable and takes command of the response. When the polluter is unknown, unwilling or unable to respond, the CCG assumes command. In this case, the M/V Marathassa initially denied discharging pollutants and there was no definitive evidence of fuel oil leaking from the vessel, classifying this incident as a mystery spill. As such, the CCG took command of the incident as the lead agency and OSC. Later in the response, the polluter may assume control if it is demonstrated they are capable of managing the incident.

Once the CCG was in command, they contracted WCMRC to initiate clean-up operations. The CCG does not currently have standing offers with the Response Organization, which can sometimes delay signing of the contract. While no delay occurred in this case, the CCG may want to consider entering into a standing offer contract to expedite the process when the CCG is the OSC and plans to use the Response Organization as a responder. The Response Organizations, regulated and certified by TC, represent Canada’s primary response capacity for oil spill preparedness and response. As per the Response Organization Standards, Response Organizations are required to mobilize resources within six hours following notification in a designated Canadian port. As per the CCG’s ER Levels of Service Footnote 24, the CCG must mobilize its resources within six hours upon completion of the assessment. Arrival time on scene will vary due to the location of the incident and resources.

In this case, WCMRC mobilized resources 48 minutes after they were activated. This response time was well within the standard of 6 hours due to WCMRC’s substantial capacity in the Vancouver area.

The CCG National Spill Contingency Plan Footnote 25 identifies three key operational response priorities: safety of life, incident stabilization, and environmental protection. In this case, the CCG SRO in Vancouver effectively followed the standard operating procedures and ensured these three priorities. He ensured his own safety as the response personnel, attempted to locate and stop the source of pollution by boarding the suspected vessel, and discussed response measures with the Response Organization, understanding the environmental sensitivities. He also assumed the role of OSC in the early hours of the incident.

The CCG SRO’s direction to WCMRC to boom the M/V Marathassa is consistent with the CCG’s powers and authorities as OSC in response to a marine pollution incident. Once the priority of controlling the source was achieved and the M/V Marathassa was successfully and rapidly boomed, the full extent of the pollution in English Bay became the next priority due to the local environmental sensitivities. The length of time that was taken to decide to boom the vessel was noted by many. Although the M/V Marathassa was not confirmed as the polluter until the early hours of April 9, it was in the area of the highest concentration of fuel oil. The intermittent nature of the discharge from the vessel is consistent with the observations of the sailing vessels that transited the area. The movement of the fuel oil in the tide undoubtedly complicated and delayed the positive identification of the M/V Marathassa as the source.

When the M/V Marathassa acknowledged it was the polluter on April 11, the vessel’s representatives could have taken over command. The CCG made the decision to maintain command and control of the response operation due to the complexity of the incident. However, the vessel’s representatives were cooperative in Unified Command.

It was noted that having a shared, comprehensive, multi-agency oil spill response plan for Vancouver Harbour that included a checklist of immediate, precautionary methods would have assisted in expediting response measure decisions. The Government of Canada announced in May 2014 that it is implementing the Area Response Planning (ARP) concept in four pilot areas across the country, including the southern portion of BC. ARP is a new planning methodology that will bring together more partners than ever to discuss risks, planning elements, and environmental sensitivities to be included in an area response plan. This process will be co-led by TC and the CCG. While many participants were familiar with the ARP initiative, they were concerned about the timelines, as they felt a preliminary oil spill response plan should be immediately developed for the Vancouver Harbour area in order to prevent future incidents from escalating.

Recommendation #8 – The Canadian Coast Guard should continue to implement the Area Response Planning pilot project, and consider expediting elements of the planning process for the southern portion of British Columbia pilot area. This plan should be regularly exercised.

The initial reports at daylight confirmed that the pollution was widely dispersed and that the management of the incident would require many more CCG staff and the support of the WCMRC team especially during the initial stages as the CCG mobilized additional resources to the incident.

Just prior to the incident, the majority of the CCG ER personnel were in Grenville Channel demobilizing from the BGZ operation and were unable to directly respond to the English Bay spill. As such, the CCG SRO was the only onsite CCG employee addressing the spill until the morning of April 9.

Recommendation #9 - The Canadian Coast Guard should ensure it has adequate staff to respond to a major marine pollution incident in any part of its region at any given time. This may involve planning and acquiring support from a national team of trained and capable responders in spill response, emergency management, and support staff, including operational communications.

The operational response proceeded remarkably well, as the source had been located and controlled with boom and the on water clean-up and the recovery operation was proceeding as expected under near ideal weather conditions. By 18:06h on the evening of April 9, the fuel oil on the water had been reduced to an estimated 667L according to a National Aerial Surveillance Program (NASP) overflight.

3.5 Incident Command Post

Key Facts

Partners indicated that in the early stages of Unified Command it was not clear which agency was in command and control of the incident. In addition, some partners were more familiar with the Incident Command Post (ICP), while others have limited exposure, which meant there were varying understandings of their roles and responsibilities. Additionally there was no capacity to offer advice or coaching to participants at the time.

Observations & Analysis

It was apparent during the initial stages of the incident that many partners were not familiar with Canada’s Marine Oil Spill Preparedness and Response Regime, leading to confusion in roles and responsibilities and misunderstanding of the polluter’s liability.

During the M/V Marathassa incident, it was apparent that some of the key partners, such as the Province of BC and the City of Vancouver, were already very familiar with using ICS. Others, however, were unfamiliar with the concept of ICS, the organizational structure, or the roles that they should play within Unified Command, which created confusion as there were varying understandings of Unified Command.

As new participants enter the ICP, a Liaison Officer should be available to assist in orientation and determining where they would best contribute based on their area of expertise and assets that they provide. Many partners noted that this function was not available at the time, which impacted individuals who may have been less familiar with ICS and unsure where and when their contribution would be necessary.

The CCG is in the third year, of a five year ICS implementation program. Many of the front line and senior leaders are in the process of receiving formal training. Although many CCG staff members were utilizing newly learned ICS skills for the first time during this incident, it was noted that as the incident progressed, management of the ICP became clearer; Unified Command members adapted to a daily routine and relationships developed as expected.

Recommendation # 10 – The Canadian Coast Guard should continue implementing the Incident Command System and include exercising with all partners, First Nations, provincial and municipal partners, and non-governmental organizations as part of the plan.

Recommendation # 11 – The Canadian Coast Guard should develop simplified quick reference tools for Incident Command Post members who are not familiar with the roles and responsibilities of Incident Command positions.

Recommendation # 12 – The Canadian Coast Guard should ensure roles are rapidly assigned and explained to members who join the Incident Command Post.

Key Facts

Once the ICP expanded to Unified Command, the number of participants became unmanageable both in terms of span of control and the physical space.

Observations & Analysis

The CCG took an inclusive approach when admitting partners into Unified Command, which was positively viewed by most partners. It was mentioned that if this event had occurred in other jurisdictions many of the partners would not have been included in the ICP and would have been briefed external to command.

It was also noted that the Emergency Operations Centre (EOC) concept may have benefited the M/V Marathassa Unified Command, which would separate the non-operational personnel from the ICP. Strategic issues that may have been difficult to manage at the ICP level could have been dealt with in a different location and led by the Assistant Commissioner. The City of Vancouver and the North Shore Emergency Management Office had in fact both established their EOCs in the early days of the incident, as per the regular ICS framework; however, due to poor communications coming from Unified Command, they felt it was necessary to close their EOCs and to join the CCG’s ICP. Had information been distributed more effectively, the municipalities would have been able to maintain their EOCs and to interface more appropriately with Unified Command.

PMV’s support during the incident was also very helpful. The ICP was set-up at the port operations centre as the CCG initially had few people on the ground while the CCG cascaded in resources.

The majority of partners noted that PMV was an ideal initial location, yet as the incident progressed, their facilities were not conducive to the growing Unified Command structure.

Recommendation # 13 – The Canadian Coast Guard should consider utilizing the Emergency Operations Centre concept at the regional level to establish a separate strategic management location from the operational Incident Command Post.

Recommendation # 14- The Canadian Coast Guard should consider pre-established Incident Command Post locations under a variety of standardized scenarios, to be included in an area response plan.

Key Facts

The CCG was mobilizing and initially lacked the coordination and control staff to effectively manage the ICP and did not have the capacity to provide a learning cell. NHQ staff was deployed later in the incident to make observations and record lessons learned.

Observations & Analysis

The deployment of a learning cell concept presents an opportunity for the CCG and its partners to learn from the incident with a view to improving in the future. Partners have agreed to provide their support in future exercises and incidents.

Although the CCG headquarters did provide support for the incident learning cell, this capacity was used internally and was not used to coach partners.

Recommendation # 15 – The Canadian Coast Guard should consider utilizing an Incident Command System coach during incidents until all staff members are fully trained.

3.6 Environmental Unit

Key Facts

EC’s NEEC is responsible for providing expert advice and support in environmental emergency response and ensuring that all the appropriate and reasonable mitigation actions to protect the environment are taken in accordance with EC’s acts and regulations, in collaboration with DFO and other federal and provincial jurisdictions. Specifically, NEEC provides knowledge on environmental priorities, local environmental conditions, hazardous substances, spill models, the fate and behaviour of pollutants, site specific expertise, weather forecast, migratory birds expertise and permitting, and provides assessments of oiled shorelines to prioritize their protection and clean-up using the Shoreline Clean-up Assessment Technique (SCAT). Specifically, DFO is responsible for identifying the potential repercussions with the native and non-native fishing industries, as well as providing habitat advice in relation to fish, shellfish and marine mammals.

One of the first phone calls the CCG SRO made was to the NEEC at 20:51h on April 8 to request trajectory modelling, which was received at 01:19h on April 9. Spill models were also available during the response from the MOE and from the Tsleil-Waututh First Nation. A request for environmental sensitivities to gain a better understanding of risks was also made to NEEC.

The NEEC program employs a coding system that follows set criteria for its response process and communication tools. A Level 2 incident only requires the NEEC to play a role remotely, whereas a Level 3 requires the NEEC to deploy on-site. An incident is upgraded when the lead agency requests the NEEC’s presence on-site, when remotely available information does not allow the NEEC to determine and monitor if the environment is appropriately protected, or there is an opportunity for training. Typically, EC convenes a Science Table or, in the case of an ICP the Environmental Unit, during oil spills.

Once Unified Command was established, the CCG had verbally requested on-site support from the NEEC. When this support was not provided, the request was escalated by the CCG Senior Management to EC Senior Management in the region. EC can self-task if the environment needs to be protected. The NEEC assessed the situation and concluded that services and advice could be provided remotely. The factors assessed included the size of the spill, the response actions underway and environmental impact. On April 18, a request for the EC NEEC official to be on site was received to render a decision on shoreline clean-up end points. An EC representative then arrived on scene on April 19, to assist in resolving the conflict in this regard.

In the absence of EC’s on-site presence, the CCG attempted to contract a local consulting firm that has experience in oil spill management, but was unsuccessful. Although EC reports that they typically do not lead the Environmental Unit (EU) during oil spills, it is Coast Guard’s view that they are the best federal agency to do so. Initially, EC and BC MOE co-led the EU; however, it became evident that this role could not be effectively fulfilled by EC remotely. Therefore, DFO and BC MOE co-led the Environmental Unit on April 13, day six of the incident. EC remained a participant in the EU throughout the incident and provided services such as site-specific forecasting, estimates of mass balance, information on fate and effects of spilled products, sampling and laboratory services, and operations advice on response and clean-up.

The Environmental Unit established daily plans, the SCAT process and sampling guidelines to assist in determining end points. While the Environmental Unit was not initially formally established, the SCAT response was established by WCMRC in the afternoon of April 9, with attention to environmentally sensitive areas in English Bay. An estimated 20 birds were impacted.

Observations & Analysis

Leadership

Environmental advice was being actively sought at the beginning of the incident by the CCG SRO, an important initial step in the effective management of any oil spill. EC’s environmental advice is independent and capable of addressing many environmental issues, from wildlife to the trajectory of the oil, the fate and effects of the spilled product, and the identification of the product. This is essential information that is required early in the spill to assist public health partners as well as other non-governmental organizations that have an interest in the protection of the marine environment.

While EC continued to participate in Unified Command remotely via teleconference, it was noted by most partners that working remotely was ineffective and detrimental to the overall response. While the advice provided was helpful, many partners felt that there was a lack of leadership in the EU. According to the NEEC’s trigger criteria, this incident did not meet the criteria for upgrading the incident to a Level 3. A NEEC representative did arrive on site when there was disagreement between partners on shoreline clean-up endpoints on the North Shore.

In many incidents, the physical presence of the highly experienced and knowledgeable officer facilitates the discussion amongst competing scientific and environmental priorities and facilitates collaboration between multiple partners. Their experience and reasonableness enables decisions to be taken and actioned by the Operations Unit in a timely fashion.

In the absence of the EC presence, the environmental partners were left to establish a lead amongst themselves and propose actions to Unified Command. However, this is not seen as the best approach and considered ineffective as several of those involved were not familiar with oil spill response and clean-up. Once EC was on-site on April 19 for the resolution of the beach clean-up standards, they were seen as very helpful and positive, highlighting that it would have been beneficial to have had this presence and leadership throughout the incident.

In 2013, the independent Tanker Safety Expert Panel made similar comments with respect to EC’s scientific leadership in an environmental response operation, particularly regarding the triggers for convening the Science Table for smaller incidents. It was noted that “in such cases, the OSC is not guaranteed immediate leadership from EC to integrate local efforts and knowledge to provide environmental and scientific expertise and advice, potentially jeopardizing the Net Environmental Benefit Analysis upon which spill response decisions are based.” The Panel goes on to say that “the coordination and delivery of Environment Canada’s scientific capability would be enhanced by their on-site presence when requested by the On-Scene Commander.”

These comments continue to be valid. EC’s on-site presence would have provided much-needed independent support and advice in the EU, would have expedited the Shoreline Clean-up and Assessment Techniques (SCAT) and environmental sensitivity decision-making, and would have added an element of public stewardship from an environmental perspective. EC recognized following the visit to Unified Command that their leadership and understanding of this complex incident was challenging over the telephone.

Recommendation #16 – Environment Canada should review its trigger criteria for on-site presence in an incident, in collaboration with the Canadian Coast Guard, particularly in complex incidents.

Recommendation #17 – Environment Canada should continue to be a leader in the Environmental Unit, providing sound and independent environmental and scientific advice during an oil spill incident.

Independence of Environmental Unit

It was noted that a private company hired by the Responsible Party and participating in the EU, was viewed as being in conflict of interest. They were seen to negatively impact discussions among some partners in the EU and appeared to be directing some decisions being put forward to Unified Command. Additionally, it was reported that their efforts appeared focused on minimizing costs to the polluter rather than trying to reach an appropriate standard of assessment and remedial actions. Some partners felt the need to obtain their own samples and hire their own experts to validate information.

Additionally, the EU was not receptive to the advice provided by the International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation (ITOPF). While ITOPF presented themselves in the role of an independent body, many partners felt that they were representing the Responsible Party. As such, the EU was having difficulties coming to consensus on advice to Unified Command.

Response Measures

In the early days of the incident, preventative booming was extensively discussed and individuals began physically drawing on maps to identify the environmental sensitivities to ensure they would be protected. Although there was a unanimous decision within the EU, preventative booming was not supported by Unified Command and never deployed. While it is recognized that the first priority is to ensure that the source of the pollution is stopped, and to conduct the on-water response, preventative booming could have been deployed to ensure that sensitive areas and public beaches received additional protection. Many raised concerns that the “wait-and-see” approach wasted valuable time and delayed effective response operations that could have prevented further contamination. This also contributed to the public perception that the response was not effective, given that there was no visible shoreline response.

SCAT and shoreline clean-up

It was also noted that the EU lacked the proper situational awareness tools and resources. Although EC provided information, many partners felt this was lacking. Additionally, the physical absence of the EC Officer made it difficult to form effective working relationships and to discuss the complex issues at hand. As a result the EU was left to establish environmental standards as they went along. This situation was noted to have contributed to lengthier decision-making processes given competing interests.

The type of product that had been released into the marine environment was known; however, the information was not initially shared with partners in the EU, who required this information to make effective decisions. This led to information gaps. Some partners felt the need to hire their own experts to assist in addressing the question as to whether the fuel oil would sink or float. Some partners were also not satisfied with the ocean-bed search for fuel oil, believing that it was not thorough enough.

It was also noted that the spill trajectory models that were provided by EC, MOE, and Tsleil-Waututh were all in different platforms and did not correctly identify the spill trajectory.

It was noted that the SCAT process was not appropriately established and was not being conducted out of the EU. The RP’s involvement in the SCAT process was also controversial as their opinion on end points was not agreed to by other partners, particularly the municipalities and the province. The municipalities felt the need to hire private contractors to draw their own samples. These competing views and priorities contributed to the view that the EU did not have clear, decisive and independent leadership. Additionally, it made sign-off of shoreline end points very contentious. Some felt that the shoreline clean-up efforts were rushed and linked to costing issues.

Recommendation #18 – Environment Canada and other levels of government should review appropriate shoreline clean-up standards that can be used for oil spill response.

Recommendation #19 - Environment Canada, in collaboration with other levels of government should ensure that the appropriate tools and resources are available for use by the Environmental Unit during an oil spill incident, such as checklists for monitoring, situation maps, sampling protocols and SCAT standards.

Information sharing and developing a common operating picture of the environment for the command and control of the response was a problem as the tools that the CCG and WCMRC were utilizing were not seen as being sufficiently thorough to enable the appropriate level of discussion and subsequent decision making. It was noted that the municipalities or the province had better tools and information to manage the incident.

Additionally, a commonly supported Geographic Information System (GIS) with all of the layers of data necessary for spill management is not readily available. Multiple partners require access to varying levels of information which often needs to be shared. A best practice, used by the CCG’s Waterway Program is the integration of these databases on a common GIS tool. In essence, partners bring their best data to the table and the CCG is able to overlay it on a common GIS database. This process could be developed further to enable its use throughout the region, in cooperation with other levels of government. The ability to develop a common visual tool identifying response progress was of great benefit for all of the partners in Unified Command and for external outreach through the Public Information Officers.

Recommendation # 20 – The Canadian Coast Guard should discuss with partners the best platform for a common operating picture for sharing spill and environmental data.

Oiled Wildlife

The public does not have a good understanding of the protocols and procedures for handling oiled wildlife in Canada, including the strategies on how to clean and rehabilitate oiled wildlife. This is the responsibility of the Canadian Wildlife Service. The independent Tanker Safety Expert Panel reflected this misunderstanding and noted the absence of a framework for the management of oiled wildlife. The Panel recommended that the Government of Canada develop and implement a strategy to provide aid to wildlife, to be incorporated in the ARP process.

Partners unanimously noted that the handling of oiled wildlife was effective in the M/V Marathassa incident. A wildlife branch was established within the EU that established wildlife response plans, and a wildlife rehabilitation centre was identified.

While there were a number of wildlife organizations participating in the branch that had competing views, and many partners in Unified Command did not have experience with oiled wildlife, this did not significantly impact the overall result. The wildlife organizations did capture, rehabilitate and free three birds out of a total of approximately 20 birds affected.

3.7 Communications

Key Facts

Partners within Unified Command were not satisfied with the collection and dissemination of information to the public and pertinent organizations regarding the spill response and its progress.

Observations & Analysis

Several of the partners mentioned the lack of timely information regarding the quantity, source and type of pollutant released into English Bay. Although information surrounding the suspected pollutant was available, there was speculation about the characteristics of the fuel oil because the information was not confirmed and communicated. Rough estimates of the quantity on the water and information on the type of pollutant were available and could have been shared to reduce tensions with public health agencies and public relation departments of partner agencies. Unified Command did not have a method of approving joint statements in this regard. Partners generally supported developing the means of joint communication from Unified Command.

Many partners noted early in the incident that the slow communications from Unified Command contributed to the public perception that the response was not progressing well.

Recommendation # 21 - The Canadian Coast Guard should ensure accurate information is released by Unified Command and/or Incident Command as soon as possible regarding the type, quantity, and fate and effects of a pollutant, including any information that is related to public health concerns.

Recommendation #22 – The Canadian Coast Guard should develop an accelerated regional approval process with respect to factual operational information during an incident, similar to the current procedures for sharing information in Search and Rescue incidents.

Key Facts

The ICS and Unified Command construct is relatively new within the CCG. The organization is in the third year, of a five year implementation program. Currently, staff members are being trained on advanced elements of ICS.

DFO departmental staff members, outside the CCG, have received very basic level ICS training. While the Communications Branch had background experience that assisted during the response, the lack of ICS training caused considerable challenges when functioning in their dual role of corporate and Unified Command communications.

Observations & Analysis

When multiple statements regarding the incident were being circulated in the media, the Departmental Communications Branch became overburdened by the dual role of assuming support to Unified Command and maintaining corporate communications. The latter role took priority and left little support for the effective release of information from Unified Command.

Additionally, it was noted that the Public Information Officer role, which is integral to effective operation, was not fulfilled in Unified Command until three days into the incident. Departmental Communications staff was on site as early as April 10.

In the absence of Unified Command communications leadership, partners occasionally disseminated information outside of Unified Command, which created conflicting messages being transmitted to the public.

Partners were looking for integrated communications leadership and identified that this would be a priority in future incidents.

Recommendation #23 – The Canadian Coast Guard should ensure the organization has sufficiently trained human resources and tools to manage Unified Command communications.

Key Facts

The CCG lacked the critical communications infrastructure to communicate and share information with its partners in Unified Command.

Observations & Analysis

It was evident within the ICP that the Government of Canada network security protocols prevented the sharing of vital information at a critical time. The CCG and DFO staff were obligated to use personal phones, laptops and email accounts to share information with partners. The security impediments extended to the inability of partners to access printers and the CCG was compelled to purchase stand-alone printers to allow partners to print documents during the incident.

In contrast, the Province of BC had a portable system equipped with Wi-Fi ports and pre-assigned email addresses that any open computer could access to facilitate information sharing within Unified Command. The City of Vancouver had similar capacity. As part of the EMBC program, both the Province of BC and City of Vancouver had prior experience planning and exercising which enabled them to communicate effectively during the incident. This issue had been identified in previous environmental and large scale incidents but has yet to be resolved.

Recommendation # 24 – The Canadian Coast Guard, with the Government of Canada IT, should develop a rapidly deployable communications and IT system that facilitates a more effective and timely electronic interface with partner agencies during an incident.

Recommendation #25 - The Canadian Coast Guard should consider establishing incident specific communication tools, such as a website and phone number, for significant incidents.

- Date modified: